Scientists make hydrogen as hard as iron

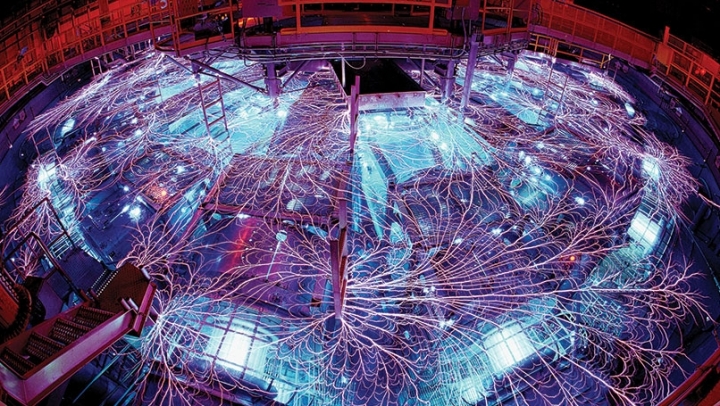

In a few highly specialized laboratories, scientists bombard matter with the world’s most powerful electrical pulses or zap it with sophisticated lasers. Other labs squeeze heavy-duty diamonds together hard enough to crack them.

All this is in pursuit of a priceless metal. It’s not gold, silver or platinum. The scientists’ quarry is hydrogen in its most elusive of forms.

Several rival teams are striving to transform hydrogen, ordinarily a gas, into a metal. It’s a high-stakes, high-passion pursuit that sparks dreams of a coveted new material that could unlock enormous technological advances in electronics.

“Everybody knows very well about the rewards you could get by doing this, so jealousy and envy [are] kind of high,” says Eugene Gregoryanz, a physicist at the University of Edinburgh who’s been hunting metallic hydrogen for more than a decade.

Metallic hydrogen in its solid form, scientists propose, could be a superconductor: a material that allows electrons to flow through it effortlessly, with no loss of energy. All known superconductors function only at extremely low temperatures, a major drawback. Theorists suspect that superconducting metallic hydrogen might work at room temperature. A room-temperature superconductor is one of the most eagerly sought goals in physics; it would offer enormous energy savings and vast improvements in the transmission and storage of energy.

Metallic hydrogen’s significance extends beyond earthly pursuits. The material could also help scientists understand our own solar system. At high temperatures, compressed hydrogen becomes a metallic liquid — a form that is thought to lurk beneath the clouds of monstrous gas planets, like Jupiter and Saturn. Sorting out the properties of hydrogen at extreme heat and high pressure could resolve certain persistent puzzles about the gas giants. Researchers have reported brief glimpses of the liquid metal form of hydrogen in the lab — although questions linger about the true nature of the material.

Read more at Science News.