Worrying: Mantle of Earth cools quicker than expected

foto: Emaze

foto: Emaze

Earth’s innards are cooling off surprisingly fast.

The thickness of new volcanic crust forming on the seafloor has gotten thinner over the last 170 million years. That suggests that the underlying mantle is cooling about twice as fast as previously thought, researchers reported December 13 at the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting.

The rapid mantle cooling offers fresh insight into how plate tectonics regulates Earth’s internal temperature, said study coauthor Harm Van Avendonk, a geophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin. “We’re seeing this kind of thin oceanic crust on the seafloor that may not have existed several hundred million years ago,” he said. “We always consider that the present is the clue to the past, but that doesn’t work here.”

The finding is fascinating, though the underlying data is sparse, said Laurent Montési, a geodynamicist at the University of Maryland in College Park. Measuring the thickness of seafloor crust requires seismic studies, and “you don’t have that everywhere; there’s nothing in the South Pacific, for example.” Still, he said, “it’s amazing that we can see the signature of the cooling of the Earth.” The finding could help explain why supercontinents such as Pangaea break apart, he added.

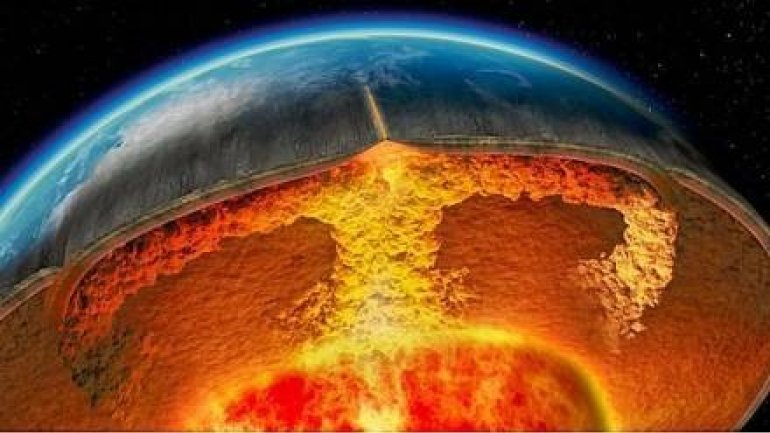

Earth’s mantle is made up of hot rock under high pressures. As material rises toward Earth’s surface, pressures drop and the rock starts melting. This molten material can spew onto the surface at mid-ocean ridges and construct new crust. When mantle temperatures are hotter, the melt zone is larger and the resulting crust is thicker. Near the upper boundary with the crust, mantle temperatures range from about 500° to 900° Celsius, writes Science News.

The thickness of new volcanic crust forming on the seafloor has gotten thinner over the last 170 million years. That suggests that the underlying mantle is cooling about twice as fast as previously thought, researchers reported December 13 at the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting.

The rapid mantle cooling offers fresh insight into how plate tectonics regulates Earth’s internal temperature, said study coauthor Harm Van Avendonk, a geophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin. “We’re seeing this kind of thin oceanic crust on the seafloor that may not have existed several hundred million years ago,” he said. “We always consider that the present is the clue to the past, but that doesn’t work here.”

The finding is fascinating, though the underlying data is sparse, said Laurent Montési, a geodynamicist at the University of Maryland in College Park. Measuring the thickness of seafloor crust requires seismic studies, and “you don’t have that everywhere; there’s nothing in the South Pacific, for example.” Still, he said, “it’s amazing that we can see the signature of the cooling of the Earth.” The finding could help explain why supercontinents such as Pangaea break apart, he added.

Earth’s mantle is made up of hot rock under high pressures. As material rises toward Earth’s surface, pressures drop and the rock starts melting. This molten material can spew onto the surface at mid-ocean ridges and construct new crust. When mantle temperatures are hotter, the melt zone is larger and the resulting crust is thicker. Near the upper boundary with the crust, mantle temperatures range from about 500° to 900° Celsius, writes Science News.