First human embryo editing experiment in U.S. 'corrects' gene for heart condition

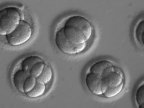

This is the first time gene editing on human embryos has been conducted in the United States. Researchers said in interviews this week that they consider their work very basic. The embryos were allowed to grow for only a few days, and there was never any intention to implant them to create a pregnancy. But they also acknowledged that they will continue to move forward with the science, with the ultimate goal of being able to "correct" disease-causing genes in embryos that will develop into babies.

News of the remarkable experiment began to circulate last week, but details became public Wednesday with a paper in the journal Nature.

The experiment is the latest example of how the laboratory tool known as CRISPR (or Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), a type of "molecular scissors," is pushing the boundaries of our ability to manipulate life, and it has been received with both excitement and horror.

The most recent work is particularly sensitive because it involves changes to the germ line - that is, genes that could be passed on to future generations. The United States forbids the use of federal funds for embryo research, and the Food and Drug Administration is prohibited from considering any clinical trials involving genetic modifications that can be inherited. A report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in February urged caution in applying CRISPR to human germ-line editing but laid out conditions by which research should continue. The new study abides by those recommendations.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, one of the lead authors of the paper and a researcher at Oregon Health & Science University, said that he is conscious of the need for a larger ethical and legal discussion about genetic modification of humans but that his team's work is justified because it involves "correcting" genes rather than changing them.

"Really we didn't edit anything. Neither did we modify anything," Mitalipov said. "Our program is toward correcting mutant genes."

Alta Charo, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison who is co-chair of the National Academies committee looking at gene editing, said that concerns about the work that have been circulating in recent days are overblown.

foto: chicagotribune.com

foto: chicagotribune.com